The world before MDS

By this I mean the world before you start the race. Or at the very least, the world before you step onto the plane to Morocco. Some people think about doing the MDS for years before they sign up. I found emails going back to 2018 of me enquiring but either not getting a place, or bottling it. For the 37th Edition I paid my deposit the moment the ‘Registrations open’ email arrived in my inbox on 23 December 2021, nigh on a year and four months before the start of the race (point to note, sign up for the alerts well in advance of registration opening!). I wasn’t missing this one. I thought i was quick off the mark, but some of my team mates had been signed up since 2019. They had been due to run the race in 2020, but due to Covid had a slightly longer prep time than the rest of us.

Registration isn’t a totally simple affair. UK registrations are handled by Steve Diederich at RunUltra/More Than Running Ltd, the UK representatives of the MDS. Most of your contact will likely be with his sidekick Sarah. The registration website is clunky and confusing and never seems to have your personal information correct. Even finding the link to log back in each time is a mission. You have to pay a €600 deposit and can then either pay the full amount or pay four instalments of roughly €1000 each. I went for the instalments. At this point I was still not sure i’d make it to the start line, so it felt less committed!

I spent the first few months trying not to really tell anyone i’d signed up, but at the same time trying to sound people out to see if anyone wanted to do it with me. No one did. I put that down to the MDS rather than it being me who asked! At this point I thought i’d just be rocking up and being allocated a spot in a tent. I had no idea how getting a place in a tent even worked. Did you just turn up and grab a spot in the first one you came to? Thankfully it’s a bit more organised than that. More on that to follow…

MDS Expo

In October, roughly six months before the MDS, was the MDS Expo. This was organised by the More Than Running crew who will email you about it a few months beforehand. It was a series of talks by various speakers, such as Rory Coleman and Elisabet Barnes designed to impart their knowledge and experience on the next cohort of entrants. The talks were a mixed bag, some useful, some not, but on balance, attending was a worthwhile experience. There were also a number of different brands there selling their kit at discounted rates. The most useful was probably the MyRaceKit team who had pretty much rebuilt their shop at the venue. If you know what you want then it’s worth attending for the discount alone. Otherwise it can be a bit of a bunfight. I made a few good buys (sleeping bag and water bottles) and a few bad ones (rucksack and roll mat). I hadn’t done the research beforehand and went with the sales patter. It’s an expensive way of doing things. Do your research, or better yet, read about our experience here.

There was also a team from Precision Hydration conducting sweat testing. Supposedly I lose 1310mg of sodium per litre of water. That’s quite a lot it turns out. It’s not a cheap test at £110, but useful knowledge when it comes to hydration management in the heat. I recommend it. Knowing about electrolytes was well outside my range before this test. You need to know about them!

Finding your tent mates

I could not have been luckier with my tent mates. Tent 77 was truly an extraordinary group who came together through a few different routes. The Expo is a great place to start if you are looking to meet other runners. I met Jason in the auditorium where we randomly got chatting and stayed in touch. You also tend to find people out on the marathon and ultra circuit in the months running up to the event. Nick and I crossed paths while running the Salisbury Plain Marathon (up there with Boston, London and New York!). The rest of the remarkable Tent 77 team were brought together through a common cause, Walking With The Wounded. Most Brits run the MDS for a charity and its a great way to meet other competitors. We arranged to meet at various events such as the Pilgrims Challenge and the North Downs 50 (both great warm up events). Once you’ve found your tent mates, sit tight until Sarah emails you requesting your names. She will then deal with the tent allocation admin with the MDS and you’ll be notified of you tent number. That tent will then become home for the week.

Day 1 - Travelling to Morocco

The Tent 77 team met early at Gatwick airport. Some of the team had spent the night in the airport hotel, others cabbed it down that morning. Most of us had met before, so that took the edge off the nerves and not knowing what we were walking into. The masses of random punters all wearing variations of MDS type kit would normally stand out at an airport, but mixed in with the stag and hen dos it suddenly seemed very normal. Seeing some of the MDS crew in the Weatherspoons at 6am with said stag dos was also reassuringly British.

There were two MDS charter flights from Gatwick, both leaving within a few minutes of each other (there’s only one plane from the UK for the 2024 edition, so be quick off the mark with registration or travel will be painful!). Arriving at Errachidia was pretty seamless. Let’s just say it’s not the busiest airport in the world so you’re not exactly stacked waiting for the runway to clear. There was however a reasonably hefty queue of MDS folk waiting to get through passport control, but no one seemed to care, it was a damn sight closer to the bivouac than the airport at Ouarzazate. Once through security, it was a case of grab your bag, check in with the rather officious MDS volunteer and jump straight onto coaches for a 90 odd minute journey to the bivouac. While on the coach we were issued with our Racebook - the Holy Bible of the route, giving us our first indication of distances and terrain. First up, a 36km day one. Then we all flicked to the Long Day. 90km. Yes, it started with a 9. A mistake perhaps? Nope, old Patrick meant business this year. With the thought of that distance on the Long Day in our minds we pulled off the road and drove into the desert. In a rather surreal turn, we passed what looked like a disused set for a Western film where you could just picture the settler family fighting to survive. A metaphor for our week ahead? I did not need convincing of this as we got off the coaches and walked straight into our first sand storm of the week.

First taste of bivouac life

Shortly after arriving there was the obligatory briefing from Patrick Bauer and his overly jovial interpreter. Get used to hearing everything twice, once in French and once in English. Also brace yourself for the full history of the MDS, shout outs to everyone (except you!) and lots of virtual high fiving. Plus the demo of how to use the poo bags. Try and get a decent spot near the front of the briefing so you get in the official photos. It’s the first proof of life your family will get! Now is also your first time to see people rocking the full white paper hazmat suit!

We stayed until the very end of the briefing and suffered because of it with a massive queue for dinner in the bivouac canteen. There’s no canteen in 2024, you’re self-sufficient from day 1, but trust me, you won’t miss anything by leaving early and getting back to your tent so you can get some food and get your head down. Some of our team chose not to risk the camp canteen for fear of the food poisoning that struck down half the field a few years before, but the food was pretty decent despite the monster queue. There was also surprisingly a beer on offer.

After dinner that’s it for the day. Time to make the most of your overly extravagant air bed (see top tips below).

Top tips for day 1:

Try and sort out your tent mates before you arrive so you have some friendly faces to travel with. The folks at More Than Running (who you book through as a UK entrant) will send an email round a month or so beforehand to ask for the names of your group. They will then sort this admin out for you so you will know your tent number before you arrive.

Stock up on food at Pret at the airport for the flight. It’s a charter aircraft so the food isn’t great. There is also a distinctly average packed lunch on the coach at the other end, so try and cater for that too.

Wear your trainers on the plane and have your rucksack as hand luggage with as much of your essential kit in it as possible. One guy lost his main bag transiting through Istanbul so had to borrow most of his kit (he managed it!).

Don’t be the tool wearing your gaiters in the airport with legs taped and ready to go. There’s plenty of time for that stuff later.

Go for a pee before you get on the bus!

You won’t have the camp kitchens in 2024, so remember to take extra freeze dried meals for a day and a half. You also might not have your Esbit fuel blocks yet, so you may need something you can eat cold.

Snap up additional bottles of water whenever you get the chance.

Take a big old blow up air bed for the first couple of nights. Make sure it is one you are happy to give away to the berbers!

Clear the stones from under the berber tent rug before you all get ‘comfortable’. Have the early finishers do this each night.

Have an extra big power bank that you can do a last charge with before packing it away in your big bag.

Day 2 - Admin day

The admin day was a weird combination of feeling like it went on forever but being over in no time at all. On your admin sheet (print it out before you arrive) you are designated a time slot for your kit check. I had a morning slot. On the one hand it was good to get it done early and get it out of the way. But on the other this is when you have to ditch your main bag so you lose all your luxuries. Anything you do keep for the rest of that day that you don’t want to lug around the whole course with you has to go to the berbers the next morning. They were pretty well supplied with blow up mattresses and in one case a blow up sofa!

The kit check was characteristically slow, with long queues in the sun. The Brits are funnelled into one queue where you go through a sequence of checks at different desks. First your bag is weighed (mine was 9.13kg - weirdly nearly a kilo heavier than when I weighed it in the UK. The sign of someone who falls for ‘just one more bit of kit’). In hindsight I would have been much more brutal with reducing weight, but more of that in our kit section. Your passport is then checked, along with the 200 Euros and for me nothing else, not even the other mandatory stuff. Then your admin check sheet is reviewed for completeness. Give this some attention back in the UK. Too many people were faffing around filling it in at the desk, holding everything up. Once through the first checks, you then have your GPS/emergency tag fitted to the shoulder strap of your rucksack. This is then followed by your ECG and medical certificate being checked and half a dozen medical questions being thrown at you. Nothing too challenging. Do make sure you get your medical and ECG done by an approved person. It would be a shocker to be chucked out at this point for an admin issue. I had mine done through Rory Coleman. The More Than Running team will send an email about this a few months before the race. It cost £100 for both the medical and ECG which seemed like a bargain compared to the private medical surgery I asked. Once through this you head to another desk where you are issued with your race numbers and some water to last you through to check point 1 the next day. This is where you need to start being careful and not wasting any water frivolously or you’ll come unstuck the next day. The final part of the checks is a quick official photo, and then you are free to go, all ready for the race. It felt slightly odd at this point that you were carrying everything you were going to need for the next week. Despite a thousand checks I couldn’t throw the feeling that I was missing something critical (I wasn’t)!

The rest of the day is spent chilling out in your tent and generally last minute faffing with your kit. Food was provided in the canteen at lunch and dinner (no longer the case for 2024 onwards). You can also pick up your Esbit cooking fuel during the day at a desk set up in the bivouac. You have to pre-order this from the MDS boutique beforehand and select the option to pick up. You can’t bring it on the flight to so this is the only option. I did end up using it for brewing up tea, but in reality the weather was hot enough to just leave the bags of food to rehydrate in the sun and that cooked it enough.

During that afternoon I was collared by the MDS media team to do a small piece to camera for the Day 1 Finishers video. This provided the home team with a fair bit of amusement. If you want to see what’s in a typical MDS rucksack, head to minute 6 of this video and watch it being described by a pro! Joking aside, these videos are worth a watch to get a sense of what life is like on the MDS.

Top tips for admin day:

You can wear flip flops to kit check, no need to go fully gaitered to the max.

Snaffle as much water as you can. from wherever you can. You need enough to last you through to CP1 the next day.

Make sure you order your Esbit cooking fuel from the MDS boutique online in advance. 1 box is enough.

Fill in the admin sheet before you get to the kit check. Do it in the UK before you leave. Too many people had to do it on the spot holding up the queue.

Have your medical docs, admin sheet, passport and 200 Euros out and ready for the kit check.

Keep your big inflatable mattress and just suck up the loss when you hand it over to the berbers the next day.

Day 3 - Stage 1, 36 km

And in a flash, here it was. Stage 1. A much longer than normal 36km to start us off. Camp life starts early on the MDS. You have to get used to people stirring at around 4.30am. Heading to the loo tents (or just off into the desert behind a bush), sparking up fires, chatting quietly (unless you are the American lady with a broken volume control in the next door tent) or just doing general admin.

You could sense a bit of nervous anticipation as everyone prepped their kit, trying to make sure it all fit comfortably - or in my case just fit in my bag at all. The pile of discarded stash for the berbers was pretty huge as luxuries were cast aside. Mattresses, power banks, Paul’s shorts. The tents were taken down around us by a very efficient team of berbers as we threw on our shiny clean running kit and took a few pre-race photos.

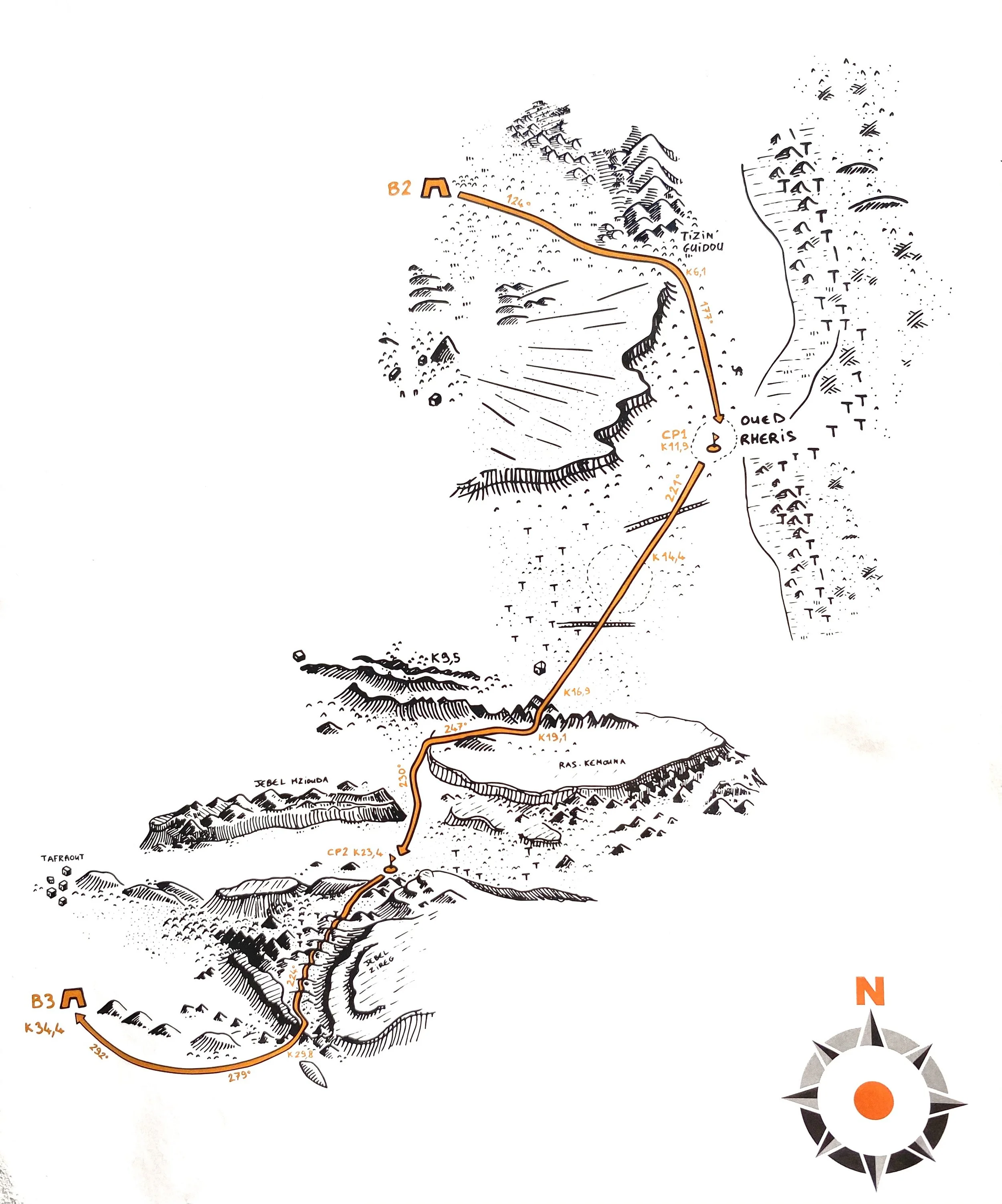

The Tent 77 team started in a few groups, soon finding our own pace. The route started off pretty gently, tempting Tom and me into running in parts. This was definitely building a false sense of security as the terrain started getting more challenging mile by mile and the heat started rising. Fast. There were two check points on stage 1, one at 13.2km then one at 24.6km. At checkpoint 1 we were supposed to be issued with one water bottle, but the MDS crew upped it to two due to the heat that was building rapidly. This was a huge relief as I was ploughing through the water already. We pretty much walked straight through the first check point, and soon four of us from the tent had found each other and were walking as a group. The last few kilometres into checkpoint 2 were across the first real set of leg destroying, sun reflecting dunes. I’d deployed my untested Mountain King poles by this point and they were an absolute God send (I took poles not expecting to use them but strongly recommend them to anyone thinking about the MDS). Despite these, however, this was where it sank in that this was going to be a very, very tough week.

When we reached checkpoint 2, I was really feeling it. Perhaps I should have actually done some heat training I pondered, two weeks too late! My race plan had been to run as much as I could on the flats and downhills and to walk the uphill parts. I was also planning on blasting straight through all the checkpoints, filling my bottles and just cracking straight on. But by checkpoint 2, my world changed. In fact, my race plan was now almost the complete opposite. I would now walk everything and rest up at each checkpoint. It was body management time. Or as one other competitor said, ‘it was now a survival exercise’. I waved off the rest of the team at the checkpoint and crept under the black goat hair tent with the mass of other runners trying to find shade. It was still a balmy 40 degrees underneath. Not great, but better than outside. I drank as much water as I could stomach while leaving myself two full bottles and forced down a KIND Fruit and Nut bar. And it really was forcing it down. I’d only tested these in an English winter. Suddenly in 40+ degrees it was like eating sawdust.

After about 10 mins I knuckled down and pushed on alone. I felt it was easier terrain than before the CP, but by this point was blisteringly hot. I was finding myself taking a couple of minutes in the shade to cool my core down whenever there was a tree big enough to provide it, and that wasn’t often. It was a long old slog into the finish with my own thoughts (at this point they were that i’ve bitten off more than I can chew).

Crossing the finish line was a huge relief. I’d hit a wall, taken a moment to sort myself out and gone again. After just under 7 hours I was back in. I was last back in my tent, but I was back, that was all that mattered.

And then the MDS struck back and brought me crashing back down to earth. I was picked at random for a kit check to make sure I was carrying the required number of calories. I was hanging out, and here I was being escorted to a random tent to unpack the contents of my bag for inspection. Luckily I had a detailed print out visible in each day’s food pack showing itemised calories and weight so it didn’t take that long. Either way, it wasn’t the ideal start to a recovery plan.

And then the desert had its turn. After testing us with a gentle sand storm on arrival, we now had a cracker. Everything was covered in sand and vital recovery time was being spent trying to stop the tent from blowing away. Thankfully we had Peter and Aubs in the tent. They sorted out the poles and ropes as the rest of us traipsed off into the desert to find big rocks to hold down the edges. They were to prove experts at tent set up and were soon in high demand from other surrounding tents. It makes such a difference to you overall comfort levels getting this right.

What a horrific first day. But we’d all come through it and you could already tell from the offers of help, teamwork and general piss taking that this was an outstanding tent.

Top tips from Stage 1:

Plan your morning routine. Shit, wash, tea, food, pack - whatever works for you. Just have your routine sorted, it will help immeasurably.

Know how to deal with a tent in a sandstorm. Or at the very least be proactive when a sandstorm hits.

Collect big rocks from out in the desert to weigh down the sides of your tent as soon as you get into camp.

Make sure you keep enough water from the night before to get to CP 1 each day. Fill both your race bottles straight away so you don’t use too much by mistake.

Be prepared to wait around at the start. Don’t be afraid to take your rucksack off while you wait.

Run your own race - don’t be tempted to try and keep up with others just because it’s day 1.

Be prepared to change your pre-race strategy if conditions dictate.

Take shade where you can. Two minutes under a tree here or there to cool down your body temperature won’t affect your end position that much.

Deploy poles early.

Have your kit squared away in case of a random check.

Having a printed out spread sheet of what food you have per day with calorie count is a must.

Drink the sugary tea at the end, it’s like nectar!

Stage 1 began at 8.30am. It already felt pretty warm by this point and everyone was keen to get started. But there is no quick start at the MDS. The start line experience is something else. Patrick and his translator side kick spent about 30 mins briefing us on the route, the weather, introducing various runners, singing people happy birthday, playing dance tunes written by one of their friends, chatting about solidarity and so on and so on. This all builds up to the obligatory blast out of Highway to Hell on the loud speakers with the helicopters and drones buzzing overhead before you finally got going.

Jebel Irhs to Oued Tijekht

Day 4 - Stage 2, 31.7 km

Life in a berber tent with eight people requires pretty squared away admin. Space is tight. But our tent had found our groove. Everyone migrated back to the same spot each day and kept their kit pretty linear within the width of their roll mat. Basic etiquette like this makes or breaks a tent. It’s just a shame snoring isn’t linear. I woke at about 3am to the already familiar snores of my darling neighbour Paul and decided to go for a pee in the desert. Oh man, what a mission that was. My legs just didn’t work. My feet hurt like anything, despite having come off pretty lightly with no blisters on day one. It took an age to walk the 30 or so yards past the outer rim of tents. How the hell was I going to repeat the previous day and walk 30+km in just a few hours time?

Now that is one of the eternal mysteries of the MDS. Come morning and it was as if the day before hadn’t happened. I was back and ready to go again (for now). I was already into a pretty good morning routine. Having your routine and kit sorted makes for a much easier life when your body is taking a beating. It’s worth practicing it if you haven’t got much experience living out of a small bag in shitty conditions. At the very least know where everything is. I had packed everything I needed for each day in single bags. Food, toothpaste tabs, sun cream sachets etc. Don’t be the admin nightmare in your tent, no one will thank you.

We all kitted up and head across to the start. All still in the race and all still smiling. We arrived on time but it seemed to take the rest of the bivouac ages to muster, driving Patrick up the wall. Unless you want to be at the front for the start there are no prizes for being at the start line first and waiting around in the heat fully kitted up waiting for everyone else to arrive. And that’s before the marathon pre-race briefing starts.

Cue Highway to Hell, and off we go again…

Oued Tijekht to Jebel El Otfal

The second stage started off pretty flat and easy going, but we soon arrived at our first real technical part of the course, the ascent of Hered Asfer Jebel. This was a long narrow rocky ridge, that rose and fell with some pretty steep ascents and descents for about 4km. There were fantastic views out across the desert on either side with the helicopters and drones buzzing around you, taking your mind off the physical exertion and making for some great photo ops. Take the time to get some photos. I used my iphone, but this gradually started to play up in the heat. I’d probably opt for as small a digital camera as i could find if i did it again.

CP 1 was down in the valley on the other side. We still felt pretty strong by this point so didn’t hang around for long here. The heat was rising fast though so I took a moment to pour some water over my head. This is a constant balance between the relief it provides and the need to maintain water to drink. I went with the brief moment of relief. Many of the team swore by soaking a Buff in water and putting it round your neck.

After the CP we soon hit a flat open plain, possibly an old lake bed that went on for over 5km. Flat as far as the eye could see. The odd motorcycle scrambler flew by in the distance. It was pretty brutal and there wasn’t a jot of shade to be found. The kicker was a blind ridge with CP 2 hidden from view behind it, so not even a target to aim for as you sweated across the plain.

As we approached CP 2 our relief at reaching it was tempered as we saw what was in store for us immediately beyond. The snake of small black dots was working its way up a brutally steep climb to the top of Jebel Otfal. The helicopter was already half way up the slope lifting someone off. Not a great sign. Tom was still feeling fresh so cracked on. Once again I needed a moment to cool down and recharge. I followed my already familiar routine, nut bar, water, rest under the shade of the tent for 10.

The climb was more brutal than I imagined. I trudged steadily in the man in front’s footsteps up the first half of energy sapping deep sand. I passed two lads who had given up and were heading back down to the CP exhausted. When we hit a small level part about half way up we all had to wait for about 10 minutes as the other helicopter came in and took another competitor off. We waved them off slightly jealously. Now the hard part. The rest of the climb was up the steepest part of the jebel, where the rocks meet the sand. A rope had been fixed to pull yourself up by. Littering the route were competitors who had pulled themselves up so far, but had stopped for respite in even the smallest bits of shade. I slowly hauled myself up, taking it in small bounds. The heat and exertion was really getting to me by this point so I was vomiting as I inched up the jebel. I sheltered briefly, but a small rockfall from people further up missed my head by inches. Better to keep moving than get a crack on the head.

I reached the top elated. I’d cracked the big one. It’s all down hill from here into the finish, how hard could it be? Pretty hard. The gulley to reach the valley floor was a mix of flat slabs of rock, sand and large boulders. The steep sides created a furnace and there was no chance to build any momentum. The terrain was just too awkward. About half way down I pulled over into a bit of shade and perched next to a group of Japanese competitors. All knackered but chirpy, smiling and chatting with each other. ‘Eat, drink, relax’ one told me. I obliged. Another nut bar, a hefty amount fo water and five minutes without my pack in the shade were exactly what I needed.

I cracked on down the gulley leaving the Japanese where they were. The bivouac came into sight in the distance, possibly 5 km away. Painfully there was a dune field in between. My joy at beating the jebel was evaporating as the up-down-up-down of crossing the seemingly endless dune field began.

‘Tell me to piss off if you don’t want to chat, but I could do with taking my mind off this,’ I said to a random guy wearing bib number 1108, his head down, plodding along.

‘Thank God for you,’ he said ‘i’d hit a low point there.’

1108 turned out to be a guy called Nick. Nick’s daughter was just about to start working at the same firm as me. Big desert, small world. We crossed the line together feeling like we’d known each other for years. I’d taken 8 hours 37 minutes. A shorter distance than yesterday, but two hours more out in the heat.

I think the rest of the tent were starting to doubt i’d make it. There weren’t far wrong!

Top tips for Stage 2

Talk to strangers. It helps, it really, really does.

Soak a Buff in water at each CP and wear it round your neck.

Unless you want to be at the front with the Moroccans, there’s no rush to be first at the start line. You just end up standing around for longer as Patrick gets into his stride.

Be linear in your tent. No one likes a kit explosion!

Take lots of photos. The landscape is extraordinary.

Wave at the live webcam at the end, your friends and family will love it!

Day 5 - Stage 3, 34.4 km

Today the race organisers moved the start to 7am due to the forecast being even hotter than the day before. The early start was good for the runners, but I knew i’d be out through the heat of the day anyway so it didn’t really make that much difference to me, apart from removing a bit of admin time in the morning.

The team made a slow amble over to the start for another lengthy briefing. By now the main point of interest was hearing how many drop outs there had been the day before. 106 was the answer. Nigh on 10% in a day. That’s usually the total for the whole event. The Jebel had taken its toll.

Highway to Hell blasted out of the loud speakers and once more we were off. It can’t possibly be harder than the day before, can it?

I later found out that i’d made the MDS instagram that morning while crossing the start line. Ok, so not a starring role, but another proof of life for the family back home. I’m not sure I look convinced by the whole thing. Point to note, if you want to be in the pics at the start, be at the edge, the photographers line the first 100m or so.

Jebel El Otfal to Jebel Zireg

The stage started sensibly enough with a fairly flat long flat section, but the relative cool soon disappeared as the intense heat caught up with us. The long, flat lake beds offered no shade and seemed to just reflect the heat straight back up at you.

I seemed to drift through CP 1 in a haze. I literally have no memory of even being there. I kept pushing on and soon approached a long slow rise up a sandy jebel. I took a few minutes in the shade of a bush before making the ascent and sat down next to a couple of Brit doctors in what quickly started to smell like piss. Goat, not human I hoped. I didn’t know it at the time, but i’d spend the next three days passing and then being passed by the same pair. It was always a morale booster to see them.

At the summit of the jebel I was overtaken by team towing a disabled child in a specially designed off road chair with a single large wheel. It was utterly humbling to watch these guys and girls taking their turns hauling the young boy up the hill. I’d found it hard enough hauling myself up there! They were something else.

Once over the hill there was a sandy valley heading into CP 2. It was hot, but not too bad going. I followed my usual routine in the CP, a brief rest, water, nut bar and try and get the core temperature down before heading on.

This is where the fun started. We skirted what felt like a lake bed with dunes rising to our left. The heat was relentless, but there was no where to hide, and not a Land Rover in sight for those craving shade and a bottle of water over the head. Or for those with thoughts of escaping this madness.

I soon came to the base of a large dune and found Steve Diederich parked up.

‘How many salt tabs have you had?’ he said bluntly.

‘One every half hour,’ I replied.

‘Not enough. Take two now and two at the top of that ridge.’

I looked over to the top of the ridge.

‘I’m not sure i’ll be making the top of that ridge,’ I only half joked.

‘Yes you will, one foot in front of the other.’

He clearly wasn’t aware of what was going on inside my head!

I thought my salt tab routine had been pretty robust, but you could see Steve was getting concerned about the heat and the number of people going down. If you’re new to salt tabs (I was) they are essentially a small pill sized bit of salt with a smooth coat to help it slide down like a tablet. In layman’s terms they make sure the water you drink doesn’t piss straight back out in sweat. They keep it in the body where it should be.

I did as I was told and cracked on. I scaled a large dune and looked at what was to come. Oh for God’s sake. We’re nearing the end and there was what could only be described as a beast of a dune field before you even get to the large jebel. The bastards.

I walked over to the medical Landy to seek some shade but there were three people on drips lying in the shade around it, so no room at the inn. The doc pointed me to a small tree just over the rise where there was a bit of shade. There were already four people huddled underneath it. I used my best French to ask to squeeze in. They thankfully obliged. I lay back on my rucksack contemplating life.

After about 10 minutes the group of French competitors got up to leave. They had walked about 10 yards when one of them turned round and came back. he kicked my leg (far too hard for my liking) and looked straight at me.

‘You have five more minutes then get up and follow me. I’ll see you at the finish.’

He could see where my mind was.

I did as I was told.

The undulating dunes weren’t as bad as I’d thought, but half way up the sandy climb I was unceremoniously hauled by the strap of my rucksack into the shade of a dune buggy by a concerned medic and stripped down. He shoved a thermometer under my armpit (thankfully only under my armpit) and poured what felt like about six bottles of water all over me.

In the time I was in my enforced break to bring my temperature back down I watched the helicopters evacuate three people off the jebel. Not great. At this point I took advantage of an additional bottle of water for a 30 minute time penalty as I was nearly out. It was a serious case of needs must.

The radios crackled and the medics suddenly lost interest in me, directed me to a small bush and jumped into the dune buggy, racing up the hill to the next casualty.

This was my chance to escape, aided and abetted by Connor. He was a Brit walking past about the same time as I was looking for my way out of medical control. We legged it. It wasn’t the fastest escape in the world, but we made pretty good time up the hill. We literally had to step over the body of one competitor being treated on the narrow path while they were waiting for the chopper to come back.

We pushed on over the peak and started the drop down to the bivouac. Steve had given us a steer that there were only 2 kms to go after the peak, and all of that was downhill.

‘Only 5 km left',’ said the medic at the next Land Rover.

‘You have to be kidding me?’

Connor and I looked at each other. We were butting up against the maximum time allowed for the day, so this was pretty dire news. We stepped the pace up and Connor got his phone out to put on some tunes. I can confirm his taste in music is awful. But it got us over the line. Which is more than could be said for the guy 2 km out who was totally gone, surrounded by medics but utterly unresponsive.

I crossed the line in 10 hours 11 minutes. The original cut off was 10 hours 30, but we found out later that they had extended it by an hour due to the heat. Either way, it was a little close for comfort.

Tom met me at the finish. I have no idea how long he had waited there, but seeing him there was an extraordinary feeling. He picked up my water for me and we trudged slowly back to the tent. I’m pretty sure the rest of the Tent 77 crew thought I was out by that point!

Still in it. Still in it.

We were all tired, filthy and looking pretty feral by that point. But delightfully so.

Top tips for Stage 3

People piss in the only shady bits there are - no idea why.

Meet your tent mates at the finish if you get back before them. It’s a morale booster like no other.

Take more salt tabs than you think you need. I started at one every 30 mins but increased from there. Take further advice on this.

Be aware that once a medic has hold of you they can keep you there until they are happy you are good to go.

Don’t always trust the Road book. We had a number of moments where distances deviated for the worse. Don’t get downhearted!

Be morale for others. That French guy under the tree got me through it with a couple of lines of broken English. Be that person.

If you decide that a pack of playing cards is too heavy and decide to cut them down into quarters, make sure you cut out the right quarter for right handed players! You’ll work it out.

You normally get up to two additional water bottles for a 30 min time penalty each. This year it was increased to three. If you’re not running against the clock and you’re struggling for water, make use of them.

Day 6 - Stage 4, 90 kms

The day of days.

90 kms had only been done once before on the MDS. Rumours were flying around about Patrick trying to make it harder to compete with the other big desert ultras like the Gobi and Atacama. Whatever the motivation, i’d maxed out at 50 km in training, so this was a little punchy. It was also forecast to be the hottest day so far.

Jebel Zireg to Jdaid

So what did I think about it? As tent media ops officer obviously I had to have an opinion! Note to anyone who uses Rory Coleman for their medical and ECG. He shaves your chest for fun far more than he needs to. Don’t let him!

The start was almost the reverse of the route we finished the day before. A gradual slope up a dune from the bivouac, before peaking and heading gradually downwards onto a flat plain. I started with Paul and Tom, but a few km in my path crossed with Nick again. He was more my speed so we watched Tom and Paul push on and set our own pace.

We were all still feeling pretty confident by this point. A bit of sand, a small hill, 5 km done, how hard could another 85 km be?

Then we hit the first long flat plain before rising up a gentle jebel. It wasn’t that bad in the big scheme of things, but you could tell the heat was rising once again. Every km down at this point was a bonus.

We dropped down into CP 1 and pushed on through without stopping for long, hitting a ridge with a steep sandy descent onto a big open plain. The floor was rock solid and dry as rock, cracked and split like elephants skin. The plain was crossed by a dirt road where a convoy of Moroccan army lorries rumbled past one after the other, the odd driver giving a thumbs up to the weirdos schlepping across this wasteland in the heat.

We were joined by another Brit who was about the same speed and cracked on together, eventually escaping the plain into a valley and starting to see some trees in the distance that might offer some shade. At last, something to aim for. Teasing us as we walked along was a sign pointing off to the right to a riad in the distance. Cold drinks and a swimming pool. Should we? Could we?

It was at this point that the second wave of the top 50 elite runners started to pass us. They were running at what looked like my 5 km pace (if i’m being generous to me!). God knows how you keep that up for 90 km.

A couple of km further on I dropped into the shade of some palm tress with a group of about half a dozen others. More piss smell. Incidentally, that wasn’t the worst of it under those trees. It turned out later that Connor was stung by something while resting there causing his leg to swell up massively.

Nick and our other walking buddy had left me at the trees and cracked on. I plodded on alone. Not for long. After a few km I found them both sheltered behind a building in the shade with a medic liberally pouring water on new arrivals. Our new friend wasn’t looking great at this point. After a brief rest we pushed on to CP 2. I head straight for the shade in one of the tents, he went straight for the medical tent. The last I heard was that he’d been put on a drip then pulled from the race by the medics.

The next section once again opened up into a large, flat, heat reflecting, energy sapping plain. At one point a full on twister just passed us by. The impending key moment was not a check point, but a cut off. All competitors had to reach 29.2 kms before 5pm to make sure everyone had enough time to climb back over Jebel Otfal during daylight hours. The organisers didn’t want to be lifting off anyone by helicopter in the dark. And there were plenty of people being lifted off.

As I approached the cut off I saw a familiar face lying up in the shade. My friend Ben was slumped up against the front wheel of the Land Rover not looking great. He had a pretty bad bout of the shits and couldn’t keep anything in. It was tough to see him looking so rubbish. He’d completed the MDS three or four times before, but this one was getting the better of him. After a few minutes chat with the doc, Ben pushed on with me across the sand dunes towards the base of the jebel. We had made the cut off. Just.

The last vestige of safety in the form of a medical Land Rover appeared at the bottom of the climb up the jebel. Ben and I decided to pause for a breather, immediate time pressure off. As we skirted the wagon, we saw Jules from my tent lying there, almost underneath it, seemingly unconscious.

‘Jules, Jules,’ I said, shaking her.

‘Jules, wake up,’ nothing. She was totally unresponsive.

This clearly wasn’t looking great and scared the shit of me. We shouted for the medic who was busy dealing with another competitor who he was putting on a drip. Ben checked for a pulse, found one, then gave Jules’ ear a vicious pinch. She moved. Thank God for that, at least she’s alive.

With plenty of nudging over a fair amount of time we got Jules back up and drinking water and getting some food down her neck. Eventually she was up and walking around. By this point we’d given Ben both of our packets of Hula Hoops (a fantastic treat for the long day - if you get to eat your own!) and he’d gone on his way up the hill.

Jules has started the day with Peter. They’d cracked through the first part, but when they reached the jebel Jules started to feel the effects of the extreme heat. Peter took her rucksack to see if he could get her over the jebel to CP 3. It wasn’t going to happen so he turned about and took her back down to the medic at the start of the climb.

‘You have to make a decision,’ said the medic to Jules and me, ‘the jebel closes in five minutes. You either go for it, or you’re out.’

By this point we were probably somewhere in the bottom 10 or so competitors in the field. The guy who came dead last was approaching fast. See the little guy in the distance? That’s him. No sign of the camels yet though!

‘Have you got another 60 km in you,’ said Jules.

‘Not sure,’ I replied, ‘have you?’

‘Not sure,’ said Jules.

We spent a couple of minutes batting the idea around and came to the conclusion that we’d much rather be timed out by not making the next check point than self selecting ourselves out. That left us about an hour and a half to get to CP 3. We were just a bit beyond the cut off at 29.2 km and had to get to 36.4 km. Over the Jebel Otfal. It was a pretty big ask, but the temperature had dropped. A bit. It was doable. Just.

‘Jules, you take the lead,’ I said, thinking that seeing as she’d been out of it less than 30 mins beforehand. I thought this was the right thing to do. Let her set the pace.

Never again. Jules had found a new leaf of life. She was reborn. Jules put her foot down and flew up the hill. She was like a mountain goat. One of those ones that has no fear of heights and has footing more sure than the French guy that climbed the empire state building without a rope. I followed on like a helpless puppy, desperately trying to keep up without looking weak and slow. I’d been shown up by Jules on Pilgrims a few months before, but this was something else. We hit the peak of the jebel within about 20 mins. What had been the downfall of many competitors during the heat of the day had been beaten. By luck more than judgement. Waiting until it was cooler had saved our skins.

Earlier in the heat of the day Nick had faced his nemesis heading up the jebel (not the bush he’s looking at) and beat it. Rugged. Lots of respect.

Jules and I passed Ben at the top. He was still looking pretty grim. We grabbed the rope and descended the jebel pretty rapidly, determined to beat the cut off. That’s when we saw the carnage at the bottom. Tens and tens of discarded water bottles surrounding a Land Rover. This had clearly been an aid point dealing with the casualties from the hill. How many had lost their dream of finishing the MDS at this point? It was gritty. It had the air of a battlefield casualty clearing station with medical equipment and dressings lying littered around. It left a mark.

We cracked on. Jules continued to set the pace. We passed a number of randoms, heads down, plodding on. We crossed dried out riverbeds, skirted thorn bushes, trudged across rocky desert.

We made it. We officially hit CP 3 just before 19.40 according to the few photos I have of us there. Cut off was 19.45. Skin of our teeth territory.

This was the first point in the whole of the MDS so far where I knew without doubt that I would finish. There may still be nigh on 60 km to go of this stage, but night was coming and with it a drop in temperature. Not only that, but I now had a team mate to walk with. Things were looking up.

We only stopped briefly at CP 3, collecting our water and green cylumes and just taking a moment to absorb the feeling of relief at having made it. We agreed to make the most of the cooler temperatures overnight to push on through and try and finish before the sun came up. That meant short stops at each check point and no sleep. We walked the first few km with Rory Coleman, just generally chewing the fat about life, his experiences on his previous 16 MDS. By that point, I already knew one was enough for me!

Darkness came pretty quickly. Jules chucked on her head torch and off we strode, just using the light of hers and trying to conserve my batteries for later. At times we were following the green cylumes of other competitors in front of us, at other times it felt like we were at the very front of the pack as we lost sight of people over hills and rises (we most definitely weren’t). It felt like an awful responsibility trying to make sure we didn’t get lost. Desperately searching for the glisten of the reflective markers as your head torch passes across them.

Walking at night in the desert is an extraordinary experience. Everyone talks about the stars. As expected, they were truly stunning. What I didn’t expect was the feeling of walking in a corridor. It was so dark that without a head torch you couldn’t see more than a few metres either side. The desert stretched out for miles, but here I was, walking along what felt like a narrow lane in Dorset, with high sided hedges. Utterly bizarre.

CP 4 came soon enough. It was truly brilliant. It’s hard to explain, but the mass of people, lying in small groups under floodlight, looking ragged, sorting out their admin brought home a real feeling of solidarity, of togetherness. We were all in this insanity together. I threw some water on to boil for food and a brew. Jules tended to her feet. The young French guy next to me asked to borrow my lighter to spark up a roll up. That moment couldn’t have been bettered. Here we were, thrashing ourselves across 90 km of desert and this guy has stuck up two fingers to it with a rollie.

It was here where we saw Vickie and Simon from tent 76. The first people we’d recognised for some time. The joy on Vickie’s face as she saw Jules will never leave me. Total surprise, total happiness. A total outpouring of human emotion only something like the MDS can generate.

‘What are you doing here? Peter said you were out,’ said Vickie in a state of stunned disbelief.

‘It’s an MDS miracle!’ she exclaimed.

Vickie and Simon were about to leave the CP, while we were just settling in for 10 or 20 mins. We couldn’t give the game away that we were still in it. We had been written off too soon…

‘You can’t tell anyone from Tent 77 if you see them, we want to surprise them when we get back,’ we asked cruelly. They agreed. Only another 40 odd km to keep this secret.

CP 4 to CP 5 took forever. I was cursing the Roadbook, my Garmin, whatever else came to mind. It always felt like it should be just over the next ridge. It never was. Until it was. And when it was, it was another moment to remember. MDS branded deck chairs were laid out across the desert in semi circles in a clearing of trees. There were people curled up on them, getting some sleep, chatting with friends and just taking some time out. We found a couple of free chairs and flopped. There was a tent handing out Moroccan tea. I grabbed a cup and lay back in the chair. Just don’t fall asleep I told myself.

Well, there was no chance of that. Harry arrived, Harry was a friend of Jules from the Half MDS the year before. Harry was an absolute firecracker of a personality. Permanently chirpy. The MDS however, was testing him. He had brutal crotch chafing. The medical teams at each CP seemed to be slightly bewildered by his requests for handfuls of vaseline. Surely they should be used to it? Point to note, make sure you road test multiple shorts beforehand. I must have tried half a dozen different pairs to get the perfect chafe free option. I went with Hoka 7” shorts and didn’t have any nether region dramas at all.

We left Harry at CP 5 not knowing if we’d see him again, he was in a bad way. CP 5 to CP 6 was dunes. Pretty much just dunes. Up and down, monotonous fields of dunes. We put our heads down and just went for it, leaving a good few hundred people behind us in the CP. From being almost in last place, we were making good progress overnight.

The first 100 yards after each CP was a nightmare. It was like I imagine walking to be when you are 90. Definitely more hobbling than walking. Our feet and legs soon warmed up as we got into our stride. That didn’t seem to be the case for one young American lad. He was only about 16 and had entered with his dad who had dropped out on day 1. Here he was, still pushing on. His walking was super laboured, but head down, he just put one foot in front of the other. It was so bad that a medical Land Rover was driving 30 yards behind just waiting to pick him up if he fell.

We approached CP 6 just as the sun was starting to rise. We were against the clock, trying to beat the heat of the next day. We still had 17 km to go at this point. On the final approach to the CP we passed a huge, newly built riad up on the hillside, most likely with a deep, cool plunge pool somewhere in it. Such a contrast to our current position that we found ourselves in.

CP 6 to CP 7 seemed to take forever. The going was pretty easy, but you could feel the heat rising minute by minute. We passed Steve again with about 15 kms to go.

‘Just three more Park Runs, you can do this,’ he said as we trudged by.

That distance felt eminently achievable. It was now just a case of us vs the heat. We stopped for a quick photo as the sun rose from behind a nearby jebel.

CP 7 was a pretty basic affair. There were just a few people under the canvas at this point. We took 5 minutes for a quick recharge then set off. The last push, as ever, seemed to take ages, as did the stretch from the moment we first saw the bivouac until we crossed the finish line. Our relief at finishing was palpable. We didn’t know it at this point, but we’d passed about 400 people overnight as we pushed on through. The cool of the night definitely was our friend.

The looks on our tent mate’s faces as we approached the tent was something else. We came in just over 26 hours. They had all written us off too soon. Again. Jules in particular had almost literally come back from the dead. You could see Peter was overjoyed to see her considering the state she had been in when they parted company 20 odd hours beforehand. Jules epitomised never giving up.

The rest of the day and night was a pretty surreal experience. Another 119 people dropped out during Stage 4, the biggest amount yet, so it became very noticeable how empty some of the tents were. Sleep was nigh on impossible during the day due to the heat, but it’s safe to say we didn’t do huge amounts.

In the evening the organiser’s laid on a classical music concert, which was the most random touch of civilisation in stark contrast to the harsh and basic environment of the bivouac. I stood, stripped back to a pair of sliders and some very skanky shorts and watched the performance, surrounded by people all probably wondering how they had finished such a gruelling stage. My favourite part is the guy walking on the right hand side. He looks how I felt! What an extraordinary day.

It was also a great opportunity to just appreciate the bivouac at night. The quiet conversations; the people brewing up or just sitting round a fire; the people tending their feet; the people queuing for Doc Trotters or the email and sat-phone tent. It was moments like these that made the MDS.

Top tips for Stage 4

Pace yourself! It’s a long old way.

Have your head torch batteries somewhere easy to access.

Push on through the cool of the night and rest up back at the bivouac.

Brew up at check points during the night, a hot cup of tea works wonders.

Take some time out of your rest to watch the concert or just experience the bivouac beyond just your own tent at night. It’s not an experience you get every day.

Day 8 - Stage 5, 42.2 kms

Only a marathon to go. How hard can it be? Well, very is the answer.

The Tent 77 crew started in two waves. The beasts Jason and Aubs had qualified for the second wave due to being in the top 200 (hence why they were chilling out in flip flops in the picture above). I’m not sure whether i’d see having extra time in camp as a benefit as you still have the same cut off times as everyone else.

The start took the usual form, but perhaps with a bit less apprehension than before the last stage. I obviously did my job as media ops officer again and snuck onto the MDS insta channel. I think I am sort of smiling! People felt a bit more confident that they were going to finish today. Peter went off pretty quickly, but the rest of the tent started as a bit of a group. Nick looked like absolute death at the start. He’d been nursing a bit of a cold throughout, but this was the worst i’d seen him. I was a tad nervous for his prospects at this point.

Jdaid to Kourci Dial Zaid

By about half way to CP 1 we’d split into a few different groups and Jules and I found ourselves together again, trying to take it pretty steadily, not wanting to overdo it and fall at the final hurdle. The terrain at this point felt pretty manageable and we were ticking off the miles.

We holed up at CP 1 for a bit of shade and to refuel. Aubs started an hour and a half behind us, but he caught us at CP 1. The man was a machine.

We saw our first real signs of Moroccan life between CP 1 and CP 2 when we were tailed by a group of small children for a few hundred metres as we passed their houses. It must have been a pretty harsh existence out here. This was also where we were passed by one of the teams pulling a disabled child. Once again I was in complete awe of these guys.

Jason caught us on a long flat open stretch between CP 1 and 2. He stayed and chatted for a short while before cracking on at a gentle jog. We were definitely slowing by this point, and we were both really feeling it by the time we reached CP 2.

The terrain after CP 2 is where it hit us. The relentless up-down-up-down of the dunes with zero shade from the heat was pretty horrific. This was then followed by a long, flat, hot, rocky plain for what seemed like miles on end. We were once again up against the clock to reach a cut off at 31.1 km. A few km out from the cut off Jules knew she was in a bad way so we took some time out in the shade of a medical Land Rover. The doc was pretty militant so wouldn’t pour any water on her to cool her down.

‘It’s supposed to be hard,’ he said to his colleague, ‘it’s an endurance race.’

Thankfully she ignored him and did it anyway.

Jules didn’t look like she was going to be allowed to leave any time soon, so hugely reluctantly and with a sick, sinking feeling I pushed on ahead to try and get to the checkpoint in time. The clock was ticking down fast. It was only a few km away, but they were some of the hardest yards of the lot. The Land Rover at the cut off was also one of the busiest I’d seen. The volunteer there was also one of the most legendary. Everyone who stopped got a bottle of water poured over their head. He was an absolute life saver. For some people, almost literally. After a few minutes I stood up ready to have a go at the next leg. Using the bonnet of the Landy to haul myself up, I turned to look back the way I had come. Like a mirage, Jules appeared, striding purposefully towards me, as if nothing had happened. She’d beaten the cut off. Just! Once again she’d risen from being on the verge of being withdrawn to being right back in it.

The section immediately after the cut off up until CP 3 was just dunes. Big old dunes. The sort where your feet slide away behind you with every step on the way up, then race away before you as you slide down them. Great for a day at the beach. Not great in 50+ degrees. We knew the CP was close, but there was no target to aim for in the distance. It was about 3 km of ‘maybe it’s just over the next crest’. It became laugh out loud territory every time it wasn’t. If you didn’t laugh, you’d cry. We just put our heads down and kept on plodding. The relief when we finally crested the last peak and saw the CP just a few hundred metres off was immense.

CP 3 was pretty quiet. A lot quieter than most of the CPs so far, perhaps apart from the last few on the long day. We knew we must be pretty low down the field, but maybe we were further down than we thought. Getting a space in the tents was a lot easier than normal, so we crawled under for a few minutes respite. Jules had run out of snacks so I offered her a choice of three different bars. She chose the Nature Valley Oats and Honey Granola Bar. One bite and it was as if I had given her a rotten kipper. The look of disgust was palpable. Not a great choice in this heat when your mouth is already dry as a walnut. They take a litre of water to wash them down at the best of times. The rest of the packet was thrust unceremoniously back in my direction.

We knew we had to motivate ourselves and push on when the Japanese guy who came absolute last on the long day appeared in the CP. The last 10 km was a grind, but one that became easier and easier the closer to the finish we got. In typical MDS style it felt so much longer than it actually was. There was one more sting in the tail for one poor competitor. 200 m from the finish line he collapsed. Medics were rushing out to treat him as we were coming in across the line. We never did find out what happened to him. I hope he made it.

And then the finish. What an incredible, indescribable moment. By this time Jules and I had now walked a hundred km side by side. What an experience crossing the line with such a robust team mate. How had we done it? There had been so many touch and go moments for both of us in different ways. For me, so many moments of doubt. So many moments where I thought my body wasn’t up to it, let alone my mind. It was all just a little surreal. But here we were, all done.

And then there’s the obligatory hug and kiss from Patrick Bauer.

Peter met us at the finish. It was so good seeing a familiar face cheering us over the line. It was a shame our photographer Jon Bromley wasn’t there to capture that once in a lifetime moment as he was supposed to be (do not use under any circumstances, he was appalling), but thankfully the official photos and those by Peter made up for it.

And the tent was complete. All eight of us had made it (Nick had actually passed us at CP 1 and blitzed the rest of it!). We were one of only four tents that were still full. Disclaimer: that was either a stat relating to the whole camp or it may be just from the British contingent. I’m taking it as the whole camp as it sounds better. Either way it was remarkable.

Top tips for the Marathon Stage

Finish. Do whatever it takes. Don’t fail now.

Day 9 - Stage 6, Solidarity Day, 9 kms

In typical MDS style, like another blind ridge, we’d finished the race, but not finished the race. Despite having been awarded our medals, there was a little sting in the tail. We now had to complete a 9km stage over dunes to show support for the MDS charity Solidarité Marathon Des Sables. Completion of the stage is mandatory or you are listed as DNF. Very sadly, there were still a few drop outs on this stage, including Connor who had helped me on stage 2. His leg had become infected and the doctors withdrew him before the start. The 2024 race seems to have ditched this stage, possibly because of the overwhelming feedback that it was a complete waste of time and didn’t do anything for the charity in question. I think this is a positive decision. I don’t think it will be missed by most.

Kourci Dial Zaid to Merzouga

We largely walked as a tent on this stage, just chatting and mutually feeling an overwhelming sense of relief at having got this far. The stage was roughly half/half flat followed by dunes. We didn’t really care that much as the end was in sight.

We crossed the finish line in a small town called Merzouga. It was slightly surreal entering a built up area having seen almost no signs of life for a week. It did also rather take the expected glamour and ceremony of completing the MDS away as you were channelled into the finish lined by locals hawking their wares. The majority were trying to sell lifts to Ouarzazate to avoid a tortuous six hours on a coach. We had prearranged a 4x4 with some of the MDS drivers the day before, so we knew there would be one waiting for us. What we didn’t know was that we’d then be handed off to a young local driver who spoke no English and by the quality of his driving probably didn’t have a driver’s licence. Be very careful about this, he genuinely nearly got us killed on a number of occasions.

If you have booked via More Than Running you’ll all likely end up in the Berber Palace Hotel. This is allegedly the best hotel in town and plays host to most of the film bigwigs who visit the various large film studios around town. Ridley Scott had been there the week before us while filming Gladiator 2, so we knew we’d probably got a pretty good deal compared to others.

Most people are in shared twin rooms. There are a few single rooms which can be snapped up if you are quick. Sarah will email round about this a few weeks beforehand. For most of us on arrival it was a case of a quick FaceTime home (now that we had wifi for the first time in over a week), a quick shower, shave, throw on some clean clothes and down to the bar. Some poor sods bags had gone to the wrong hotels, so spent the first night walking round in the hotel dressing gowns. I don’t think they cared, they were clean at least. After wearing the same kit for about 9 days, it took a good half hour in the shower before I felt human. Then that first beer and a few slices of pizza was something else. We’d done it.

Day 10 - Rest day, 0 km

Day 10 was a full day to ourselves at the hotel to rest and recover before flying home. It was a bit like decompression after an operational tour. Everyone had their own way to recover. Mine was a sun bed, a pool and bucket loads of rosé. The MDS crew had set themselves up in a hotel down the road where you could pick up your finishers t-shirt and buy branded tat. They also has a Doc Trotters outpost that a few of the team took advantage of. Putting to bed a myth here, you absolutely are allowed in the pool at the Berbere Palace Hotel, but not if you have open wounds. We wondered down first thing to try and get it done early, but the queue was out of this world, so we sacked it off and prioritised pool time. Despite the number of competitors at the hotel, there were remarkably few getting stuck into the sun bed and rosé scene. I’m sure there were other things to do around town, but I didn’t find them!

That evening there was an awards dinner at the hotel for the British contingent. Steve Deiderich hosted and gave out a few awards. He also ran an auction of some various MDS bits to try and raise some money for the MDS charity. It was a touch lame and could have been done so much better and raised so much more, but it was great to get the whole team together for a dinner.

Despite many people’s best efforts, the crowd thinned out pretty quickly as people head off to bed, utterly exhausted after the last week. A few of us made a decent fist of staying up, but it caught up with us eventually.

Day 11 - Flying home, 3211 km

The final morning was all pretty functional. Packing up and clearing out of the hotel. The airport was only a few minutes drive from the hotel in coaches, so took no time at all. The check in queues were, however, as expected. Long and slow. It has a small tat shop and that’s it apart from an old guy with a trolley selling snacks (cash only) once you get through security.

Arriving back in Gatwick was a moment I don’t think any of us will forget. Saying goodbye to the team as we all picked up our bags was emotional enough, then walking out into the arrivals hall to be greeted by a crowd of families and friends with banners and cheers was enough to bring a tear to the eye. This was the power of the MDS, this showed what it meant to a much bigger group than the competitors themselves. The friends and families who had lived it for months or even years. The training, the sacrifice, the stress of tracking their friend or family member on the race itself. This was the MDS in all its weird, indescribable glory.

And that was that. We’d done it., We’d beaten the odds as a team and all made it. Never again…?

Thinking about it but have questions? Drop us a line.